Michal Schonbrun, MPH

December, 2024

Females are born with 1-2 million (immature) eggs, more than they will ever need. During our 35-40-years of reproductive capacity, approximately 10-20 eggs are stimulated every month. Under the influence of the hormone estrogen, these eggs grow inside fluid-filled sacs called follicles. During a days’-long marathon race to develop quicker than the others, one egg emerges -from the most developed follicle- and this is what leads to event known as “ovulation” (In the case of fraternal twins, there could be two ripe eggs). In the western world, ovulation occurs approximately 400 times during a woman’s life.

Considering that this is something so common and central in the story of human fertility and reproduction, it is hard to believe that only in 2008 were photos of (human) ovulation actually seen. For the first time, in real time, the release of a ripe egg from a human female was observed, on camera, as it bulged out of an ovary. The images were captured, by chance, during a routine operation in a Belgium hospital. A 45- year woman was undergoing a hysterectomy when doctors realized she was ovulating. They called in a camera crew with specialized equipment and history was made. It was only in 2008 that scientists learned (or unlearned) that ovulation is not necessarily the momentary, explosive event in one-second time they thought it was. Rather they learned it was a process that can actually take up to 15 minutes! The story and photos can be viewed here on the BBC website.

Fast forward (or slow-forward), sixteen years later, to Oct, 2024, when a video of ovulation was produced by researchers from the Max Planck Institute in Germany. Alas, the video is not of a human female egg but that of a mouse! (Didn’t we say that progress moves slowly)? This video represented the first time that the entire process of ovulation had been caught on camera, in real time. As the event unfolded, under a microscope, the researchers were able to track three separate phases:

In the first phase, they saw how the size and shape of the expanding follicles changed. The observers learned that hyaluronic acid secretion is essential for this growth and for the success of ovulation. When the researchers blocked the production of hyaluronic acid researchers, the follicles expanded less, and ovulation did not occur.

In the second phase, the team noticed how the primary follicle’s smooth muscle cells in the outer follicle layer caused the follicle to contract. When the team inhibited the contraction of these muscle cells, the follicles failed to contract and ovulation did not occur.

In the third phase, the surface of the follicle bulged outward and eventually ruptured, releasing the follicular fluid, the cumulus cells, and, finally, the egg.

After ovulation, the remaining follicle tissue (that produced estrogen to prepare for ovulation) forms into a new structure called the corpus luteum (“yellow body” in Latin), which produces the hormone progesterone. When the corpus luteum produces progesterone, the uterus prepares for the possible implantation of an embryo, even if a pregnancy does not occur. If the egg is not fertilized or if the fertilized egg does not implant, the corpus luteum stops working and within 10-14 days, the uterine lining sheds and a new menstrual cycle begins.

*

*Illustrations of the ovary and ectopic pregnancy, Rainier de Graff, circa 1672

To get perspective on how we reached the not-so “modern age,” we need to look back a few hundred years. During the 17th century, a Dutch man named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, became the first recognized microbiologist. He invented the modern microscope and was among the first to document sperm under a microscope . His work and writings shaped an entire generation and beyond. Following a centuries’-long mindset which viewed women’s bodies as inferior or less than men’s bodies, Van Leeuwenhoek believed that only male sperm were directly involved in procreation. He rejected the idea that women produced eggs or that they could contribute something to the process of fertilization! Fast forward three hundred years and we find science textbooks (into the 1980’s) describing the story of how the egg meets the sperm, based on gender stereotypes from the Darwin era. The egg was portrayed as the “damsel in distress,” waiting to be rescued by a male sperm. Most of us learned that the strongest, fastest, and most active sperm is the one that penetrates/conquers the egg, who is just a weak and passive bystander in the act.

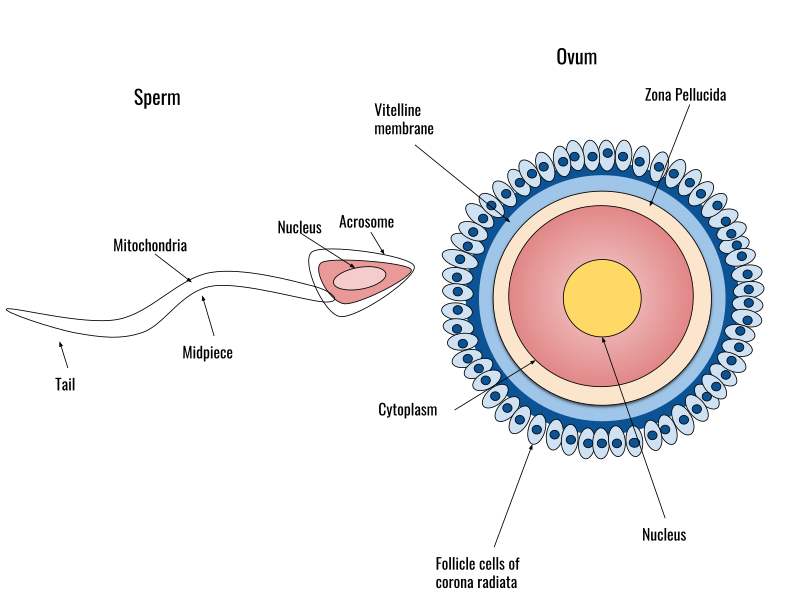

Only in the past few decades has science abandoned its previous attitudes and military motif language about how fertilization occurs. Since the 1990’s and through the 2000’s, research continues to shed light on the significance of the egg in the process of fertilization. For example, we now know that the egg is surrounded by a barrier of “corona cells” which act like bouncers in a club: these special cells filter out the sperm and decide which sperm will be let in!

The language of science continues to shift as women’s body parts become more understood. So we will patiently wait a bit longer, for researchers to capture an actual human ovulation on camera. This small example about the pace of scientific discovery reminds us of Rachel E. Gross, the science journalist, and her ground-breaking book, Vagina Obscura (2022), which takes the reader on a whirlwind journey charting what the history of medicine and science have taught us about female bodies. She makes the most astute and outrageous observation which can be turned into a question: “Why do we know more about the surface of (planet) Mars and the bottom of the ocean floors than we do about the vagina and other body parts (of human females)?” The answer: women’s bodies and natural processes have been viewed (historically) as less important and too complicated.

Let us hope that in less than another sixteen years, women’s reproductive organs and events will be less shrouded in mystery and that viewing the act of human ovulation becomes more common, leading to renewed awe in the female form and also to new advances in reproductive technologies.

Sources

New insights into the ovulatory process in the human ovary, 2024

Vagina Obscura, Rachel E. Gross, 2022

Scott Pitnick et al, Post-ejaculatory modifications to sperm (PEMS), 2020

Martin, Emily. The Egg and the Sperm: How Science Has Constructed a Romance Based on Stereotypical MaleFemale Roles, Signs, University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Accreditation recognized by The Association of Fertility Awareness Professionals

* All illustrated characters are taken from “The Monthly Cycle,” a short film by Ada Ramon and Ofek Shamir.

Quick Links

The information presented on the site is for educational purposes only and is not intended to replace medical advice from a qualified doctor or other health professional. For convenience, the information is written in the feminine form, but refers to anyone born with a uterus and ovaries, including those who do not identify as women

Contact Me

Join Our Newsletter

One Response

With what we understand now about ovulation and conception, there is no reason to not totally impress upon pregnant couples that what has occurred is miraculous. There have been articles saying that the egg sends out chemical determinants that signal to certain sperm or individual sperm that they can proceed versus stay back. The idea that the joining of the egg and the sperm is not casual or random, makes couples feel a sense of destiny or this child is coming because it had to be this child and not any child. They feel closer to the child knowing this. What is done therefore, when it is conceived in a petri dish? And that when the one chosen sperm penetrates the lining of the egg, the heads of the other sperm hovering nearby, are detached from their tails. Is this true? This is all so interesting.